I was warned to fear the Gypsy. For those unfamiliar with the term in its theatrical context, a “Gypsy” is a dress rehearsal for Curt and other members of the EST staff to attend so that they can evaluate the progress of the theater’s current production to make sure it is fit to open the following week. Curt, I was informed, had a reputation of being a particularly harsh critic – so much so that one member of EST affectionately rechristened the Gypsy “How Long Until Curt Makes You Cry?” The most frequent advice I was given before the Gypsy of my play A Bitter Taste was, “Bring a box of tissues.”

I was warned to fear the Gypsy. For those unfamiliar with the term in its theatrical context, a “Gypsy” is a dress rehearsal for Curt and other members of the EST staff to attend so that they can evaluate the progress of the theater’s current production to make sure it is fit to open the following week. Curt, I was informed, had a reputation of being a particularly harsh critic – so much so that one member of EST affectionately rechristened the Gypsy “How Long Until Curt Makes You Cry?” The most frequent advice I was given before the Gypsy of my play A Bitter Taste was, “Bring a box of tissues.”I knew as I sat down for our Gypsy rehearsal that things would not go smoothly. A bout of the flu had meant a lost week of rehearsals for the cast. Nor was there – for various and temperamental reasons - an excessive amount of love and devotion amongst our actors. They were under-rehearsed, under-prepared, still fumbling through lines and generally adrift. Two hours later, after sitting through the most painful dress rehearsal of my brief career, I watched the actors wheeze across the bloated finish line that marked the end of what had once been my play. Curt politely thanked the actors for their time and talent; he then took the director, the co-artistic director, and me into his office to talk.

If Curt had wanted to cancel the opening (which was less than a week away), he would have had my full support. I had, by this late point in the game, lost most of my faith that my New York theater debut would be a successful one. It wasn’t simply the lost week of rehearsals and the unsteadiness of the actors that dampened my hopes. It was the fear that this unsteadiness that seemed to permeate the production stemmed from the fact that no one seemed to understand what my play was about - and no was getting closer to figuring it out. To explain it in the simplest terms: I thought I had written a battle to the death; I was getting something closer to a very intense thumb-wrestling match.

“What is this play about?” Once we were all assembled in Curt’s office, that was the first question he asked. No threats. No warnings. No catalogue of flaws of what he’d just suffered through. Just a simple question, “What is this play about?” My heart stopped because I thought he was being literal. I thought we had failed at the most basic level of storytelling and he had not understood the plot (even though he’d seen a workshop production a year earlier at Carnegie Mellon University). A moment later I realized Curt was not talking about plot. He was asking – as all good theater practitioners do – what we were trying to communicate. Before we could answer, Curt proceeded to tell the room what my play was about.

Playwrights – particularly fledging playwrights looking for their first production – can spend a lot of time explaining or defending their work to people. But in Curt’s office that day, someone other than me did the explaining. More importantly, he got everything right. Everything I felt was important in the play, everything that needed to be communicated to the audience – he understood it all. And it didn’t take him more than five minutes to impart this to those gathered in his office. What he was essentially saying was “Kevin’s play is about X, Y, Z and what I’m seeing is A, B, C.”

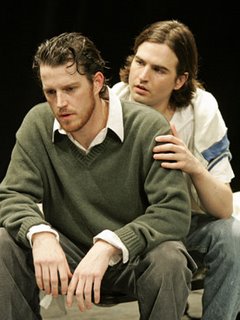

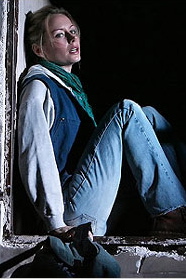

The production had gotten off track, and Curt knew it. He knew it wasn’t just line flubs and missed blocking that was standing in our way. He knew what he had just seen wasn’t my play, but some spiteful doppelganger posing as my play. The production had strayed from the play. (His wittiest observation that I recall concerned the role of the underage male prostitute, “This kid lives on the street, and you’ve got him dressed like he orders his clothes from L.L. Bean.”) Curt might not have been saying anything new to the people assembled in his office. But it served as a wake-up call. We had five days before we opened and a lot – a lot – of work to do to get this play back on track. It wasn't just Curt lighting a fire under our asses, it was Curt reminding everyone in that room that there was already a fire - in the play that I had written - and we needed to use that.

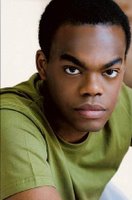

The production had gotten off track, and Curt knew it. He knew it wasn’t just line flubs and missed blocking that was standing in our way. He knew what he had just seen wasn’t my play, but some spiteful doppelganger posing as my play. The production had strayed from the play. (His wittiest observation that I recall concerned the role of the underage male prostitute, “This kid lives on the street, and you’ve got him dressed like he orders his clothes from L.L. Bean.”) Curt might not have been saying anything new to the people assembled in his office. But it served as a wake-up call. We had five days before we opened and a lot – a lot – of work to do to get this play back on track. It wasn't just Curt lighting a fire under our asses, it was Curt reminding everyone in that room that there was already a fire - in the play that I had written - and we needed to use that.That hour in Curt’s office was the first time since coming to New York that I felt like I was taken seriously as a playwright. Only two weeks earlier the photographer taking publicity shots for A Bitter Taste overheard some of the more risqué dialogue and remarked rather snarkily in front a full room of people, including the actors, “Do your parents know you write this kind of stuff?” (Imagine such a remark being addressed to Neil LaBute or Adam Rapp or Christopher Shinn and expecting them to take it in stride.) I was used to being treated like a kid who didn’t know what he was doing. But Curt trusted the text. He trusted the play I had written. He not only understood the play, but championed it to room full of people, telling them, “This is what this play is about. Do THAT.”

I have great memories of A Bitter Taste and rather depressing memories of A Bitter Taste. I have pleasant memories of Curt, and I have frustrating memories of Curt. What I will remember the most, though, is the first time I was treated like a playwright. For that memory, I will always be grateful to Curt.